JAN 26, 2016

David Letwin

How do you identify yourself?

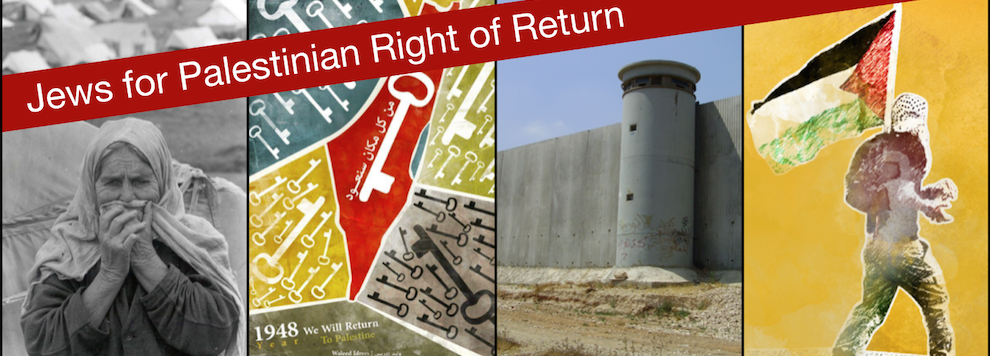

I think of myself as a social justice activist. I come from a family of activists going back to my grandparents, who came here from Russia in the early 1920s. That’s not the only way I identify myself, but that’s one of the main ways I think about myself. I’ve been involved in the arts for many decades, and that’s a crucial part of my identity, too. I was a musician for a while. I’ve been involved in the theater for over thirty years as an actor, director and writer. Now, I teach theater at an arts conservatory. I guess the three things I identify as now are social justice activist, artist and teacher. A lot of the work I do with the group Jews for Palestinian Right of Return is centered around poster art. I’ve become more interested in how art can be used as a medium to reach people, often times more than just long speeches and statements of principle, although those can be important as well. I’ve often found that a well-designed poster or meme can go viral across the web when an article might only be read by a handful of people.

When I travel to other places and people say, “What are you?” I don’t say, “Oh, I’m a social justice activist.” They’re clearly looking for some kind of national identity. I guess I say I’m from the United States. I don’t like to identify with the word American because it has a lot of implications that I don’t like There’s this idea that America means the United States or that those things are synonymous, whereas saying I’m from the United States is just a statement of fact. There is a place called the United States. It is acknowledged as a political entity, and that’s where I was born and grew up. For Jews, one of the historical expressions of anti-Semitism was that Jews were so-called rootless cosmopolitans. It was the idea that Jews don’t really attach themselves to any country. You still occasionally hear that idea of, “Oh yeah, Jews don’t like to identify with a country of origin.” Historically, that was a way of denigrating Jews. I don’t think of myself as a rootless cosmopolitan. It’s just that I’m anti-nationalism of the oppressor, so I feel ambivalent about identifying with the nationalism of countries that have a history of white supremacy, corporate capitalism and imperialism. I think of that nationalism as fundamentally different than the nationalism of the oppressed, so I have no negative feelings when I hear someone saying, “I’m Palestinian” because that’s a response to oppression and to racism—the identity of the oppressed—and that’s much different than identifying nationally with the oppressor groups. I don’t want to do that. I don’t proudly walk around going, “Yeah, I’m an American.” That feels totally wrong to me. I think I’ve always wanted to identify by a set of values. The values have been more important to me than religious or national identities.

I also do identify as a Jewish person. A comrade of mine once said, “As long as there’s anti-Semitism, I will regard myself as a Jew.” I think it’s probably true that if anti-Semitism fully disappeared from the world, I might not be invested in thinking of myself as Jewish at all. To me being Jewish is largely about identifying with a history of oppression. I’ve had to think about this a lot as the years have gone by. When I say to people, “Oh, I’m Jewish,” I’ve come to realize that what I mean is, “That’s right, I lost family in the Holocaust.” “That’s right, I’m part of that group that suffered a lot of historical oppression,” as opposed to believing in the rituals of Judaism, which I do not. We celebrated Hanukkah and Passover when I was growing up, but I haven’t been to a Seder in many years, and it doesn’t interest me now. I have no desire to go to a Seder or to celebrate the Jewish holidays separate from whatever political issues can be raised about equality and justice. If a Seder were dedicated to talking about how Zionism has oppressed Palestinians, I would be all in favor of going to a Seder, but I don’t feel connected to the ceremonies of Judaism, in themselves.

I still do identify as Jewish, which is why I’m part of this group called Jews for Palestinian Right of Return. I feel that as Jews we have a particularly useful role to play in undermining Zionism. A tactic Zionism has used to try and gain credibility for itself has been to say, “We represent all Jews.” As a Jewish person, I feel I have a role to play in undermining Zionism as a racist doctrine by saying, “No, you speak for Zionists, not for Jews.” Now it’s true, many Jews are Zionists, and maybe they speak for Jews that are Zionist, but they don’t speak for the idea of the Jewish identity because not all Jews are Zionists, and I am explicitly anti-Zionist. I’m opposed to Zionism. That’s why I feel it’s okay to have a group called Jews for Palestinian Right of Return, not from a need to separate ourselves, but the need to use our Jewish identity and privilege as a way of helping undermine Zionism.

Do you feel like you are misrepresented in society and the media?

I only wish I had more visibility that I could get misrepresented. As an individual, I don’t feel misrepresented, but I think the idea of being an anti-Zionist Jew has been misrepresented as a self-hating Jew or being anti-Semitic, being a Jew Hater. The idea of being an anti-Zionist Jew or a Jew who supports Palestinian human rights has been misrepresented in the mainstream media and by society. I’m trying to think if I’ve ever personally felt like I’ve been misrepresented. I’m not sure that I have. I’ve never read any articles that said, “David Letwin said this, and he believes this” and gone, “Hey, that’s a misrepresentation.” I only hope that someday I do achieve some kind of level where someone would misrepresent me. I think that would be a step forward in terms of getting ideas out there. To a degree, I also identify as a Marxist—a Marxist in terms of my critique of Capitalism—and I think Marxism has been misrepresented. In other words, I think a lot of the value systems that I connect to have been misrepresented by the media.

How have you experienced oppression personally?

I don’t know if I do feel it personally if by personally you mean distinct from other people. I feel a common oppression in the sense that all of us are being oppressed by a capitalist system that exploits us, that is destroying the environment. All of us are suffering to some degree, and some people much worse than others. When we discuss these issues in class, we talk about, “Well, what does it meant to view yourself as someone who is oppressed?” “What are some of the markers you use?” “How do the police deal with you?” “Do taxi drivers stop for you?” “Do you hear people making horrible jokes about you?” “Are you not treated fairly or equally?” I can’t say I feel any of those things. I think to be white and male and straight and upper middle class is to not feel a lot of conscious oppression, except to the degree that you are concerned with the future of the planet or the collapse of the economy, which might mean that all of us lose our jobs while there’s a 1% or while there is an exploitative ruling class that is protected from that kind of thing. I feel oppressed in the sense that capitalism oppresses us all. Separate from that, I don’t really feel oppression. I feel on the other hand like I lead an incredibly privileged life, but again, even people who lead privileged lives still suffer oppression from people who wield the most power in a culture. If the ozone layer completely falls apart and we all get skin cancer and die, a lot of the distinctions about people being privileged are all going to go away. It will be the end of us all.

Can you talk about your involvement in the Palestinian Liberation movement and the organization Jews for Palestinian Right of Return?

I’m one of the co-founders for the group Jews for Palestinian Right of Return. We are more of an idea or a rallying point for a set of ideas and ideals than we are a membership-based group. We are mainly an online presence. We have a Facebook page that any day now is going to get its 16,000th like. We regard those as our supporters, but they’re not members in the sense that we do not participate in meetings. There’s just a handful of us doing the work. We started this formation because we thought it was important to connect Jewish identity to the idea of Palestinian refugee right of return. The refugee right of return we’re speaking of refers to the roughly 750,000 Palestinians who were ethnically cleansed by Zionists to make way for the so-called Jewish State with all of those non-Jews living there. Palestinians call this the Nakba, or Catastrophe, in Arabic. So that’s the first part—the ethnic cleansing—and the second part is that Israel will not allow these refugees or their descendants to return to their homeland in direct contravention to international laws and UN resolutions that reaffirm the Palestinian right of return. UN Resolution 194 explicitly reaffirms the right of Palestinian refugees’ right to return, yet Israel has been denying that resolution since 1948.

Why do you think the international community lets Israel get away with that?

Because the UN is largely run by the “major powers.” The Security Council is run by the most powerful countries in the world. These countries exercise a great deal of influence in the General Assembly as well. They can both bribe and threaten less powerful countries to support their positions, which is precisely what happened with the UN General Assembly resolution to partition Palestine in 1947. The only reason that resolution passed in the General Assembly was because the ruling powers at the UN—mainly the United States—threatened and twisted arms and bribed enough countries to endorse the partition resolution. It would never have passed had the US and other powerful countries not threatened and bribed other countries to endorse it. And even with all of that bribing and threatening and arm twisting, the resolution is still illegal in the sense that the UN does not have the right and did not have the right to partition the land in the first place. So the legal basis for the State of Israel—the UN Partition Resolution 181—has no validity. It was an invalid resolution in the sense that the UN didn’t have the mandate to partition Palestine any more than it can come here and partition Brooklyn. It can’t do that, so it could not have partitioned Palestine to begin with. That could only have been decided by all of the residents of Palestine, and Palestinians made it clear they did not agree to partition. They were completely within their rights to take that position.

The UN is politically corrupt in that way. It’s essentially controlled—or often times key aspects of resolutions are polluted—by the power that the major empires have running the UN. I think that is why for over 70 years the world community has not said, “Hey, wait a minute. This completely contradicts human rights.” Also, to the powerful empires of the world—The United States, Western Europe—Israel is an important watchdog state that plays a role in defending Western imperial economic and political interests, so billions of dollars in aid and lots of military equipment are given and sold to Israel. The Israeli military and the entire system is propped up by massive amounts of foreign aid—including advanced weaponry—because Israel plays a salient role in defending Western capitalist and imperial interests in the Middle East.

If you look at The Universal Declaration of Human Rights or look at what is now accepted as human rights and universal law, you cannot ethnically cleanse, and you cannot deny refugees the right to return to their homeland. In fact, you cannot even have a state like Israel to begin with because the entire notion of a Jewish state in Palestine—a state that both allocates and denies human rights on the basis of the ethnic or religious identity—violates international law and more importantly the rights that underpin international law. International law only has any meaning to the degree that it reaffirms the underlying rights. That was something that Martin Luther King made very clear in his letter from a Birmingham jail where he said explicitly that rights precede laws. And he said by way of analogy, “If I went to Nazi Germany in the 1930s, would I have been beholden to follow the anti-Semitic laws of Nazi Germany?” He said, “No! Yes, they were laws, but they were not based on human rights, on valid rights.” So on that basis, Israel—and by no means only Israel, other regimes too—is based on violations of internationally accepted human rights.

Can you talk about the history of Zionism?

Political Zionism means the drive for a Jewish state as opposed to older forms of Zionism that just talked about returning to the Holy Land, the land of Zion. Political Zionism is the idea of Jewish settlers setting up a colonial state in Israel for world Judaism. That has its roots in the 19th century ideals, European ideals of nation states based on ethnic or “racial” purity. That’s really what the impulse for Zionism was. It was to establish the same kind of state in the Middle East that they saw white Europeans and white Americans having. Those were states based on racial purity and racial supremacy. They said, “We want one of those states.” It didn’t arise out of nothing. Jews were an oppressed minority in Europe. Zionism gets its political definition in the 1890s with the publication of Theodor Herzl’s book Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) in which he sort of lays out the principals of political Zionism, which was fifty years before the Holocaust. Now, even before the Holocaust there was a lot of anti-Semitism, but most Jews in Europe did not respond to anti-Semitism by becoming Zionists or Jewish nationalists. They responded by trying to assimilate or by trying to come to other countries like the United States, which were not seen as anti-Semitic. Many of them were drawn to the arts as a way of finding acceptance of their identity. People have always asked, “Why are there so many Jewish artists?” Many Jews became involved in revolutionary politics—communist politics, socialist politics. They saw the liberation of Jews as being connected to the liberation of all humanity—from capitalism, from racism and from colonialism.

A very small percentage turned to Zionism in the beginning. Zionism was a mix of things. It was for sure a desire to escape what they saw was going to be this non-ending situation in which they would not be treated as equals in the West. Zionism didn’t say, “That’s terrible. That’s racist. We should fight against that.” Many of the Zionists said, “It’s perfectly normal. We don’t belong in the West. We don’t belong in these other countries. The anti-Semites say that we’re not loyal to these countries we live in.” And a lot of Zionist said, “Yeah, that’s true. We’re not loyal to these countries because we’re Jews, and we’re always going to be loyal to ourselves as Jews first. That’s why we need to go to a place where we can have a Jewish state, and we can set-up the same kind of country that all of those other countries have.” They didn’t see racism as a fundamental aberration of the human spirit. They saw racism as to some degree normal. They would say to people, “Anywhere we go, we’re going to be seen as outsiders because that’s what happens in life. If you don’t belong in the culture, people will hate you, and rather than fight against that, why don’t we go to a place where we can have our own separate identity as a state? The land will be Jewish. The cows will be Jewish. The trees will be Jewish.”

They spoke in terms of setting up a Jewish identity in a Jewish state. They saw themselves as not doing anything different than what a lot of the rest of the colonial, imperialist West was doing. They would look at Germany and say, “Well, Germany talks about how this land is for German people, and England talks that way. Look what the American colonists did. So we’re not doing anything different.” Of course the great irony there is that that’s exactly what Hitler said when he was justifying what the Nazis were doing in Eastern Europe during the Second World War. He said, “We are not doing anything different to the Eastern Europeans and the Slavs than the white settlers did to the Red Indian.” I’m not saying Zionism is the same as Naziism. I want to go on record making that clear because people tend to look for those kind of comparisons, “Oh my God. He said there was no difference.” No. There is a difference, but there’s also similarities in the sense that all of these racist ideologies have their roots in these nineteenth century ideas that there are races, and the races need to be separate and pure. That’s what the Zionists often talked about. That is why Zionists hated Jewish people who wanted to assimilate much more than they hated anti-Semites. They saw the real threat as being Jews who didn’t want to remain separately Jewish. They were scared that was going to undermine the Jewish people.

So these Zionist settlers left Europe. They came to the Middle East because they said that’s where our roots were not only from the Romans two thousand years ago but from when the Arab culture came in twelve hundred years ago. That’s where some of the Zionists would date the diaspora from. They’d say, “Oh, we left after the Arabs came in.” They did that partly to make it seem as if there had been a Jewish presence in the Middle East even after the Roman expulsions, which by the way, some historians contend did not even happen. These Zionists came to settle in the Middle East with the ultimate goal of setting up a Jewish state. We need to be clear. A Jewish state doesn’t just mean a state where Jewish people live. It doesn’t mean a state where Jewish people are treated equally. It means a state where Jewish people are in control. To exercise that control, you need to get rid of the people who aren’t Jewish, and for whatever number you allow to remain, they have to be treated as third class citizens. The Palestinians who managed to remain in Israel—even though they were made citizens in 1966—are still not treated as fully equal. There are over fifty laws in Israel which directly or indirectly privilege Jewish citizens over non-Jewish citizens. And if you say to Israelis, “Hey, you have over fifty laws that privilege Jews over non-Jews,” they don’t say, “No we don’t.” They say, “Yeah, of course we do because that’s the only way that we’re going to be able to preserve a Jewish state.” So in a sense, it’s the Israelis themselves that admit that Israel is a racist, apartheid regime. They don’t like to use that language. Sometimes they do. There’s a video out there that I saw on YouTube where a young Israeli Jewish woman is saying, “Look, if it’s racist to say this is a state for Jews, then yeah I’m a racist.”

When they first started migrating to Palestine, there were already Jews who had been there for thousands of years. How did they feel about the migration? Did it affect their life negatively?

That’s a good question. I am not an authority on that, but the Jews who were living there were called Mizrahi Jews—Jews who were born to Arab countries. They’re called Sephardim as well—Ashkanazi versus Sephardim. Sephardim refers to Jews who practice in the Spanish tradition. Ashkanazi Jews are Jews who practice in the German tradition. There were Jews living there, and they had been integrated into Arab culture. Many of them spoke Arabic, so many of them identified as Arab Jews. That’s how they saw themselves. For the most part, they were fully integrated into Arab culture. Does that mean they were always treated as fully equal? No. If you look at world history, everywhere you look in the world there have been dominant ideologies, often based on religion. Islam was the dominant religious ideology in the Middle East from the 600s on. Islam as the dominant ideology had certain privileges for Muslims that didn’t exist for other people, but Jews and Christians were called people of the book because they came from the Abrahamic tradition.

Jews were not always legally treated as fully equal. Although, sometimes they were. It depends on where you look at in the Middle East and what era you’re talking about. Sometimes there was oppression, and there were other times when Jews did very well and often served in high positions of the government. Take for example the country of Iraq, when Iraq gained independence from Britain in 1932, there were Jews who served in the highest level of the cabinet. Jews thrived in a lot of the Middle East. That’s not to say that there wasn’t oppression, but it was not anti-Semitism. It was not based on the idea of hating Jews as a race in the modern use of the term. It was based on the idea that there had been a ruling religion of Islam, and anybody who wasn’t Muslim was not quite at the same level. You find that kind of hierarchy everywhere in the world throughout history.

Mizrahi Jews suffered from the prejudice of Ashkanazi Jewish settlers, who often saw Mizrahi Jews as below them, inferior. They saw them as being corrupted by their generations in the Arab world. In fact, a leading Jewish Zionist sociologist was a man named Arthur Ruppin. He’s called the father of Jewish sociology. When Ruppin died in 1943—this was while the Holocaust was going on—he was busy at work on a book explaining in scientific terms why European Jews—Ashkanazi Jews—were genetically superior to Jews from the Middle East based on measurements of the skull and nose. It’s now a fairly discredited pseudoscience. Historian Gabriel Piterberg has pointed out the irony that here was this leading Zionist, and what was he mostly concerned about in 1943? Proving the European Jews were racially superior to Jews in the Middle East. The Kibbutz movement not only refused to allow Arabs to live on the Kibbutz, they also didn’t typically allow Mizrahi Jews in the Kibbutz. Basically, the Kibbutz movement was for the European Jews who were seen as being more developed. How did Jews living there respond to this wave of European Jews coming in who saw themselves as superior? I think that would be a fascinating study.

Once the State of Israel came into existence, Zionism brought a huge backlash against Jews in the Middle East because they brought with them all of these racist ideas of Jewish separatism, Jewish only associations and the idea of a Jewish state. It provoked a lot of other Arab countries—particularly after 1948 when Zionism kicked out all the Palestinians. There was a backlash against some Jews living in some Arab countries. They became identified with this Jewish state. Israel itself undertook a campaign to alienate Jews in Arab countries to get them to leave and come live in what is now Israel. They wanted as many Jews as they could get, and they also needed a working class Jewish population to do all of the menial jobs that they didn’t think European Jews would be willing to do. In Egypt, there was something called the Lavon Affair, named after the Israeli defense minister. The Israelis sent Special Forces into Cairo to set off bombs in Jewish communities with the idea of scaring the Jewish population to get them to leave. They were found out. The Egyptians found some of the Jewish agents. That set off a huge scandal. The Israelis later called it the Unfortunate Affair. It was part of a broader campaign. In Yemen, they paid money to Jews to get them out. In Iraq, the same thing happened.

There have been some protests within Israel by the Ethiopian Jews. Is there racism within the Jewish community toward people of a darker complexion?

Zionism has produced a kind of white supremacy. It’s not just a Jewish supremacist country. It’s also fundamentally a white supremacist country in where the darker your skin, the more likely you are to not be viewed as equal. There have been protests by Ethiopian Jews in Israel because they’re not treated equally. With Mizrahi Jews, there’s been a very interesting dynamic because some of them want to believe that they have somebody themselves to look down on, so some of the Jews who are the most vehemently anti-Arab are the Mizrahi Jews. In the United States, why did poor whites in the South who had every interest in forming solidarity with poor blacks become incredibly racist? Because they wanted somebody to look down on, because they themselves were looked down on by the culture. You see that dynamic in Israel as well. It’s the need to believe that you’re not at the bottom. And of course that’s encouraged because if you divide, you conquer. In some of the Iraqi Jewish websites I’ve seen, there are complaints like, “In Iraq, we were treated better in some ways than we are treated in Israel. We had a more integrated life in the Arab countries.” A Jewish guy did a study recently of how Arab people responded to the Holocaust. He found Arab names on some of these monuments to righteous people who had protected Jews, and then he started to do some research.What he found is that in some Arab countries, Arabs played active roles in protecting Jews and preventing them from being sent off to Germany.

As far as Jews within Israel today, there’s a great amount of support for Israel. Why do you think they support what’s going on today?

Well, I think it’s probably for a number of reasons. Some of the reasons are understandable. Because of the Holocaust and the legacy of anti-Semitism, it’s been easy for Jewish people to tell themselves, “Look, the world hates us. No matter what we do, we’re going to be hated, so we can’t worry about what non-Jews think of us.” Another reason is that they’re privileged. There is a system that privileges Jews over non-Jews, a racist structure, which was best exemplified most recently by the so-called Nationality Bill, sponsored by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The purpose of this bill was to reaffirm the idea—in his words—that Israel was a state of one people and one people only—the Jewish people. Well, there you go. 20% of Israel’s citizenry is made up on non-Jews, so what the prime minister just said was, “This country does not belong to all its citizens. It only belongs to the 80% who are Jewish.” It would be like the president in the US saying to sixty million people in this country, “This is not your country.” We would regard that as a statement of unacceptable racism.

Some of us would.

Right.

I went to a lot of Free Gaza marches in 2014 when Operation Protective Edge was going on, and at every single one of them, there would be a few Jewish people that happened to be in our path that would actually stop and yell at the protesters. There was a concentration of anger that I hadn’t seen at marches I had joined for other causes. I especially saw this on one march we went on through the jewelry district in Midtown Manhattan. They were mainly Jewish/ Israeli owned businesses on this street. We were chanting Free Gaza, and tons of people came out of the stores enraged and ready to fight. They were faced with mostly white, non-Palestinian protesters. It felt like we were about to be attacked by an angry mob. Can you talk about why the anger is so explosive?

I think it’s a very important thing to examine. I have my own theories about that. I think some of it is the anxiety they feel about the Holocaust and the fear that our future is at stake. I don’t think that explains all of it, though. I think they are particularly troubled when they see Jewish people doing it because then it forces them to question their value system. It forces them to say, “Why would these Jewish people be talking about Palestinian rights?” I think the reason they respond so angrily is because deep down they know something is wrong with their position. My experience with people has been that when you have equal access to express yourself and you get that angry at people, it’s usually a sign of guilt. It’s one thing if you come from an oppressed group that has been historically marginalized and oppressed, and you’re so angry that it comes out in rage. I can understand that anger with Black Americans or any number of different groups in America that have been treated unequally. Today at least, many Jewish people in the West are affluent. They have access to power and self-expression. Jews are not really an oppressed group in this culture. Now, when you’re in that situation and you get that angry because people have raised a question of equality for other human beings, because they have dedicated themselves to human rights, when their only “crime” is they are committed to equality for everybody, when you are that angry about that, I don’t think that’s explained by the Holocaust or decades of anti-Semitism in Europe. I think the only thing that really explains that is shame and guilt. That’s my analysis.

Have you experienced any backlash from being involved in Jews for Palestinian Right of Return?

Yeah, I’ve been at rallies where people have yelled at me. I’ve had a couple Jewish friends on Facebook unfriend me or not want to have contact. I’ve had Jewish friends tell me, “I just can’t talk about it because it’s too painful.” I’ve never encountered a Black person saying that they can’t discuss racism or police abuse because it’s too painful. I think the difference is that when you know you’re right, when you know you have justice on your side, you want to talk about it. You don’t want to shut down discussion. You want to be heard. But when you’re concerned about whether you have justice on your side, when you doubt that you have justice on your side, that’s when you want to shut down discussion. I think many Jewish people are aware on some level that Israel and Zionism do not have justice on their side. Whereas I think people in, for example, the Black Lives Matter movement know that they have justice on their side, which is why they want to have the discussion, why they want to have their voices heard.

In Israel, is there a resistance movement within the Jewish community against Zionism?

There are anti-Zionists. I don’t know if a resistance movement is a way to describe it. There’s a group called Boycott from Within. We haven’t even talked about the Boycott, Divestment & Sanctions (BDS) Movement, which is the biggest Palestinian grassroots movement calling for Palestinian rights. The other reason that we call ourselves Jews for Palestinian Right of Return is that Palestinian right of return is one of the three main rights demanded by the BDS movement. One is the end of the 1967 occupation. The second is full equality for Palestinian citizens in Israel, and the third is Palestinian refugee right of return. Many leaders of the Palestinian movement along with BDS leaders and activists have said that the right of return is the single biggest right because it gets down to the whole problem of the Jewish State. It addresses the fundamental underlying issue of the lack of equality. As Jewish people, it’s our responsibility to be a Jewish voice promoting that right, particularly since there are not many other Jewish voices in this country doing that. So to answer your question, there is this group called Boycott from Within that’s a largely Jewish group. It’s an Israeli group calling for a boycott of Israel, and there are other anti-Zionist Jews in Israel, but not many. First of all, I think it’s very hard to be anti-Zionist because the state comes down on you. There’s a law they’re trying to pass in Israel—I’m not sure if it’s been passed yet—but they’re attempting to criminalize support for Boycott, Divestment & Sanctions. I think that has made many Jewish people worried who might otherwise support it. There are some Jewish people in Israel that speak out against Zionism, but a very, very, very small minority in Israel.

Can you talk about the issue of illegal settlements in the West Bank?

A lot of people look at Palestine and say, “Oh, the problem is the 1967 occupation with all of the illegal settlements in the West Bank.” That is a huge problem. You have these Jewish only settlements in which Palestinians are kicked off the land, and these settlements are supported by the government. They’re racist in their very conception because they’re Jews only. That’s racism. But you have the same problem within Israel. There are all kinds of laws which are racist in terms of housing in Israel. For example, since 1948, no new Arab villages have been allowed to be built in Israel. Whereas scads of new villages for Jews have been able to be built. There are also situations where Jewish housing settlements and communities in Israel can turn away people, can deny people entry into the community because they are seen as socially incompatible. What they mean by that is that they’re not Jewish. Then you have the removal of the Bedouins from what the Israelis call the Negev Desert. They removed them so that Jewish settlements can be built on their land. So it’s not just in 1967 occupied territories. It’s also in the 1948 territories of Palestine. In both parts of historic Palestine—in what’s called Israel or in the 1967 territories—settlements are often run on racist principles of Jewish supremacy. How Israel controls the land is one of the main ways that the racist doctrines of the Zionist State are promoted and protected.

Now, it is true that a very small section of the land can be sold to anyone. I think it’s around 6%, but most of the land of Israel is put aside in perpetuity not for the Israeli people, but for the Jewish people, and that’s another way that the racism of Zionism manifests itself. If Zionism weren’t racist, that land would belong to all the people of Israel regardless of their religious or ethnic identity, but it’s not. It’s put aside for the Jewish people. We shouldn’t accept Jewish only settlements anywhere in historic Palestine. In other words, Jewish only settlements are illegal anywhere. Just like in this country, white only settlements are illegal. It doesn’t matter whether it’s Alaska, Michigan, Mississippi or New Mexico. There are no states where you should be able to have white only settlements. This should be illegal in historic Palestine just like it should be in the Arab countries or anywhere people live. If you are a Jewish citizen of Egypt, you shouldn’t be denied equal rights on that basis. Any citizen of any country should be given equal rights. What you have in Israel is a situation where non-Jewish citizens are denied equal rights because they’re not Jewish. So it really shouldn’t be a distinction of the illegal settlements in the West Bank. It doesn’t matter if those settlements are in the West Bank or inside Israel. Either way, there should be no racist Jewish supremacist settlements or state structures and institutions of any kind.

Israel’s reaction to the people in Gaza is quite violent compared to their reaction to Palestinians in the West Bank. Why do you think that is?

Well, I think part of it is that Gaza has become a symbol of resistance. My impression is that when people in Gaza elected Hamas, they elected Hamas not necessarily because they’re Islamic fundamentalists—although I assume that was part of it—but because they were seen as resisting Zionism. They were seen as resisting Israel. Israel needs to collectively punish the Palestinians of Gaza because their resistance is a rallying point for all other Palestinians. What they’re trying to say is, if you’re Palestinian, we hold you collectively responsible for resisting us. Also, they are using Gaza as an example. They politically couldn’t get away with launching a bombing campaign like Operation Cast Lead on Arab villages in Israel or even the West Bank, at least at this point. They find other ways of oppressing Palestinian citizens of Israel—through the legal system, through the land allocation system and a whole host of other methods. One of the other ways that Palestinian citizens in Israel are treated unequally is that there are a lot of rights and benefits that you could only get if you are a veteran, and non-Jewish citizens of Israel are not allowed to join the army. They do allow the Druze to serve, but if you’re a Palestinian or Arab citizen in Israel, you’re not drafted into the military. Therefore, you do not get a number of benefits—education benefits, health benefits, housing benefits, employment benefits—that you would otherwise get if you served. And there are two education systems. In almost every major way, Arab communities in Israel are not funded as well as Jewish communities. That’s intentional because they see themselves as the Jewish State. That is why at Jews for Palestinian Right of Return, we try to make it clear that we don’t make distinctions between the mistreatment of Palestinians in Israel and the mistreatment of the Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. There are differences, but underlying those differences is the same problem, and that is the Zionist State. If we want to stop the mistreatment of Palestinians by Israel in Gaza, we have to go to the same system that is also mistreating Palestinians of Israel. It’s all one system. In Gaza, they’re not being punished because Hamas sent rockets over. They’re being punished because they resist the idea of being oppressed. They’re an indigenous people resisting their oppression.

As someone living and growing up in the United States, I didn’t find out the truth about this issue until I went to college. I guess it was in 2002 that I found out the details of the oppression that is going on. I post a lot about it myself, and I’ve gotten some resistance from some Jewish and non-Jewish friends. In America, there’s a lot of support for Israel. Can you talk about why that is?

I think some of it is connected to the legacy of anti-Semitism. Although, I always find it interesting that many of my Jewish friends who support Israel have never experienced any anti-Semitism in their own lives. I think that’s an interesting question. What explains it? I think if you take away the Holocaust, there probably wouldn’t be an Israel. There probably wouldn’t be all this support for Zionism, so the Holocaust clearly influenced the need for a Jewish State in the eyes of Jewish people. That need in their eyes coincides with the desire of the ruling class of the United States to have a watchdog ally helping keep control of the region, so that the West can control the resources—the oil.

I think there is a lot that the American public doesn’t understand about the dynamics of our government, but the media is very instrumental in creating that misinformation.

Right, because the media is a watchdog for the regime, for the government. There’s been pushback. Even in the New York Times, which has huge problems with its coverage of Israel. In fact, a lot of the reporters who cover Israel are Zionists. There was an issue recently with one of the leading Times reporters on Israel. He’s Jewish, but more to the point, it turns out his son served in the Israeli military.

And he was an American serving in the Israeli military, right?

Right. Any Jew from around the world can automatically become a citizen of Israel. That’s one of the things that we point out. Palestinians ethnically cleansed in 1948 cannot return to their homeland, but a Jew from Brooklyn who has never been there can become a Jewish citizen. So the American media colludes with the American political class, the American ruling class, the 1%, to support its agenda. There’s also in this country the Christian fundamentalist community, and they support Israel because of their theology. They believe that before rapture can happen, Jews have to be returned to Israel. There’s great Christian fundamentalist support for Israel on that basis. That explains why a lot of Christian fundamentalists—who have their own anti-Semitic issues to deal with—support Israel.

So they’re not doing it for the Jews. These Christian fundamentalists are only really interested in themselves.

Ultimately, because my understanding is that once all those Jews get returned, and then the rapture comes, all those Jews that don’t convert are going to get sent to hell anyway.

Exactly. Do you think we’re capable of overcoming the oppression that Palestinians are faced with?

I don’t know the answer to that other than to say whatever the answer is, we have to try. There are some encouraging signs. When I first started getting involved in this years ago, the discussion was a lot less open than it is now. Now, increasing numbers of Jews are becoming supporters of Boycott, Divestment & Sanctions and the growing groups like Jewish Voice for Peace, Jews for Palestinian Right for Return and International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network. There are spaces for these groups now. You are interviewing me. That wouldn’t have happened ten years ago. I think one of the most encouraging things is the connection between all of these various solidarity groups, the connection between white supremacy in this country and the struggle of people of color to liberate themselves, people of color in this country connecting their struggle to liberate themselves against racism in this country to the struggle of Palestinians to liberate themselves from Zionism. That’s been a very encouraging sign.

What do you think is a good solution for historic Palestine?

I believe the just solution is what’s called the one-state solution. Jews for Palestinian Right of Return endorses that as a solution. The idea is one democratic state throughout all of historic Palestine with equal rights for everybody, regardless of identity. The formulation we use, which we got from Palestinians, is: A democratic state from the river to the sea—meaning the River Jordan to the Mediterranean—with equal right for all. That’s the only solution that tackles the underlying problem of a racist Zionist regime. Just like the only just solution for South Africa was one that tackled the underlying problem of the apartheid regime. And that is why we oppose the so-called two-state solution because it does not get to the heart of the problem. All it says is, “You can still keep your apartheid Jewish state, but just on less of the land.” And that’s not justice.

With the oppression the Zionist State has created historically—similar to the problems colonialism and slavery created in the United States for the Native and African Americans—how do you think we can right the inequality as far as reparations and making sure that everybody gets an equal share? Do you have any ideas of how that might be organized?

No. I don’t pretend to know all of the practical ways of organizing that. The way I look at it is that if the will is there to do justice, the practical ways can be sorted out. People always say to me, “Now how will all the refugees return? How will that work out practically?” I say, “I don’t know exactly how it would work, but if you’re committed to the principle, we’ll find a way to make it work.” That’s pretty much true of all these issues. In other words, what stands in the way of justice is not practical problems. What stands in the way of justice is people’s unwillingness to see justice as a desirable goal, people’s unwillingness to commit to the principles of justice. Once you commit to the principles of justice, you can make it work. I think that’s true pretty much everywhere.

I like what you said earlier when you said that you don’t even know if you’d identify as Jewish if it weren’t for this history of oppression, and even some current forms of it that still exist. If on a global level we are committed to the principles of justice and making sure that everyone has a democratic voice and equality no matter what their religion or race, if people come to find that they don’t need to identify with something because of oppression, what do you then think we are capable of?

I don’t know how to answer these big questions about the future. I just would say that it would be great if we could eliminate the sources of racism and eliminate the sources of oppression, gender, race, ethnicity or whatever word you use to describe those kinds of injustices. Do I think we’ll have a perfect world? Of course not because human beings are not perfect. As Kant’s saying goes, “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, nothing straight was ever made.” People are not going to create a perfect society. There’s always going to be tension. There’s always going to be problems to resolve, particularly when there is scarcity of resources. But as Martin Luther King said, “The arc of the Universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” And so all we can do is try to struggle and defend those principles of equality whenever and wherever we can, particularly when people being denied their rights are calling out to the world for solidarity. And you can’t do that as an activist on the basis that you’ll be successful, that someday you’ll achieve this Utopian existence. You can only do it on the basis that it’s the right way to live life.

Interview by Stacy Lanyon

http://attheheartofanoccupation.blogspot.com/

http://buildingcompassionthroughaction.blogspot.com/

https://www.facebook.com/stacylanyon

https://instagram.com/stacylanyon/

https://twitter.com/StacyLanyon

http://stacylanyon.com/

Posted 26th January by Stacy Lanyon

Elements of Oppression

FEB

16

Yajaira Saavedra

Photo by Erik McGregor

How do you identify yourself?

I identify myself as Indigenous, Native American, Mixtec from Oaxaca, Mexico. I’m a matriarch, which means that I’m following in my grandmother’s footsteps. It means that I want to be like her. I want to raise my family to be hard workers, to be individual workers, to sustain ourselves, to be independent and pass on the Native American traditions—language, food, clothing and belief system. I govern myself. Being a matriarch is more about the way I was raised. My mom worked full-time just so that she could be able to provide for my family, and she somehow managed to keep the culture alive in us even though we were exposed both to the American and the Spanish culture once we migrated to the United States.

FEB

2

Khury Petersen-Smith

How do you identify yourself?

I identify as an activist.

Do you feel like you are misrepresented in society and the media?

Yeah. Last night, I got a phone call, and it was a pollster. They were conducting a survey. He asked me a series of questions about my politics and how I identified.

JAN

26

David Letwin

How do you identify yourself?

I think of myself as a social justice activist. I come from a family of activists going back to my grandparents, who came here from Russia in the early 1920s. That’s not the only way I identify myself, but that’s one of the main ways I think about myself. I’ve been involved in the arts for many decades, and that’s a crucial part of my identity, too. I was a musician for a while.

JAN

12

Susie Abdelghafar

March for Palestine, August 20, 2014, Brooklyn, NY

Photo: Stacy Lanyon

How do you identify yourself?

I guess as Arab American. I’m starting to say African Arab American because technically Egypt is in Africa. There is an ongoing debate about whether or not Egyptians should be considered African America or Arab American. I’m also Muslim. Saying that I identify as Muslim is definitely a struggle and oppression in itself.

JAN

5

Nicholas Levis

Photo: Stacy Lanyon

How do you identify yourself?

I hate these boxes. I am a fellow in the PhD program in history at the graduate center of the City University of New York. I was born into a very Greek extended family in Astoria, New York and learned the language as a baby, went to a Greek-American elementary school, a New York public high school and a fancy college for all of the good it did me.

DEC

16

Vanessa Rivera De la Fuente

How do you identify yourself?

I am a woman. I am feminist. I am mother. I’m a curious woman because I’m always seeking to learn from different things. This is something that is very typical in me—the searching for knowledge and the asking for why. I am always asking for why. Sometimes people get really upset. For me, it’s more important to know the reason and to try and understand how things work, how people work, how people see. I’m kind of a researcher of life.

DEC

1

Bahaa Qasem

How do you identify yourself?

I’m a Palestinian, but at the same time, I am a super hero simply because I live on this small piece of land, which is called Gaza, and all the governments around the world planned to imprison us in the big siege. What makes matters worse is that I went through three brutal wars. I graduated from English literature at Islamic University, and I am working as a translator in the media.

NOV

18

Wendell Headley aka Earl Lee Day

Photo: Stacy Lanyon

Who are you?

First of all, I’m a human being—a poverty stricken human being—living in an unconventional environment. It’s unconventional for status and quality to be living in basically a drug infested environment and a non-ethnic similarity environment. I’m in a community where my ethnicity—which is a Black man—is not totally accepted in predominately Spanish neighborhoods.

NOV

10

Amy Majagua’naru Ponce

Indigenous Peoples’ Festival/ Pow Wow, Randall’s Island, New York, October 10, 2015

Photo: Stacy Lanyon

How do you identify yourself?

I identify as a Boricua Taino from the island of Puerto Rico, which was originally called Borike, which is why we call ourselves Boricua. I’d like to think that I was placed on this earth to bring beauty through art, through music, through culture and through the work I do with people.

NOV

3

Mariam Barghouti

How do you identify yourself?

As a Palestinian woman. I grew up between the privilege of the West where I’m a carrier of a US citizenship and the occupation here. Even at twenty-three, I still cannot grasp what Palestinian means and what my identity is because it’s so directly associated with occupation, or the resistance, or oppression that I don’t really have the time to look beyond that. As women, we’re constantly fighting two oppressions.

Loading

Dynamic Views template. Powered by Blogger.